The hidden network

Explore our interactive mapTL;DR

Since February 2024, the World Watch Cyber Threat Intelligence team has been working on an extensive study of the private and public relationships within the Chinese cyber offensive ecosystem. This includes:

- An online map showcasing the links between 300+ entities;

- Historical context on the Chinese state entities dedicated to cyber offensive operations;

- An analysis of the role of universities and private companies in terms of capacity building;

- A focus on the ecosystem facilitating the acquisition of vulnerabilities for government use in cyber espionage campaigns.

Note: The analysis cut-off date for this report was October 22, 2024.

Authors: Piotr Malachiński & World Watch team

Introduction

Between 2023 and 2024, our World Watch Cyber Threat Intelligence team issued over 35 advisories and updates concerning zero-day vulnerabilities exploited by Chinese threat actors. These account for 41% of all advisories with a high or very high threat level (equal to or above 4/5 based on our scoring scheme), representing a substantial portion of the critical threats potentially facing our customers. Whether aimed at directly compromising organizations for intelligence gathering or broadly infecting edge devices to build botnets or operational relay box (ORB) networks, the exploitation of vulnerabilities by Chinese state-linked threat actors underscores their considerable offensive capabilities.

The existence of state-sponsored threat groups operating under the Chinese state's direction has long been well documented. Since Mandiant's groundbreaking 2013 report exposing APT1, numerous other Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) groups have been linked to Chinese government entities, particularly the People's Liberation Army (PLA) and the Ministry of State Security (MSS).

Given China's authoritarian governance, characterized by extensive party control over social, political, and economic spheres, one might assume that cyber operations by these APT groups remain strictly in the hands of the state. However, China's offensive cyber capabilities are, in fact, supported by a complex and multi-layered ecosystem involving a broad array of state and non-state actors.

In February 2024, a leak at a Chinese company Sichuan i-SOON provided further evidence of the extensive public-private cooperation in support of Chinese state cyber operations. From official contracts to internal communications, the leaked documents exposed i-SOON's role as a long-time contractor for the MSS, carrying out cyber campaigns against targets in over 70 countries, from France to Rwanda or Nepal.

China's engagement with non-state actors is not confined to private companies. The government has a longstanding tradition of integrating top universities into national security efforts. The "Seven Sons of National Defense", for instance, are key academic institutions affiliated with the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, contributing significantly to the state's defense R&D efforts. As it turns out, this collaboration also extends to cyberspace, as the academia increasingly supports state-sponsored cyber campaigns, often focused on espionage to advance China's political and economic interests.

This report offers a comprehensive overview of China's cyber threat landscape, with a particular focus on the integration of civilian and military cyber capabilities. It contextualizes these actors' activities and builds on existing research by leading experts and insiders, including Dakota Cary, Adam Kozy, Eugenio Benincasa, the Natto Thoughts research team, and the Intrusion Truth group. The report also introduces a detailed, interactive map created by the authors, which visualizes the connections between hundreds of public and private entities, spanning government, industry, and academia.

This research focuses on the participation of state and non-state actors in the structured cyber activities emblematic of APT groups. As such, discussions on financially motivated cybercriminals, including extortion and ransomware groups, as well as hacktivists, will be limited to their connections with state-sponsored entities. Additionally, while disinformation and malign influence operations are related to Chinese cyber-enabled activities, they fall outside the scope of this analysis and will not be covered here.

The report is structured as follows:

- Section 1 provides an overview of the key state actors involved in China's cyber threat ecosystem, including the Ministry of State Security (MSS) and the People's Liberation Army (PLA), with an emphasis on their historical development.

- Section 2 explores the complex roles and impact of private companies on state-sponsored cyber operations, as well as the internal dynamics of cooperation and competition within the sector.

- Section 3 examines the role of academic institutions in APT campaigns, highlighting their function as the state's hub for offensive security research and development, as well as a crucial source of new talent for state-sponsored cyber efforts.

- Section 4 presents a case study on China's software vulnerability gathering system, showcasing the cooperation between public, corporate, and academic actors.

- Section 5 introduces the authors' comprehensive database, presented as an interactive map that visualizes the intricate network of relationships between public and private entities involved in China's cyber operations.

State institutions and capacity building process

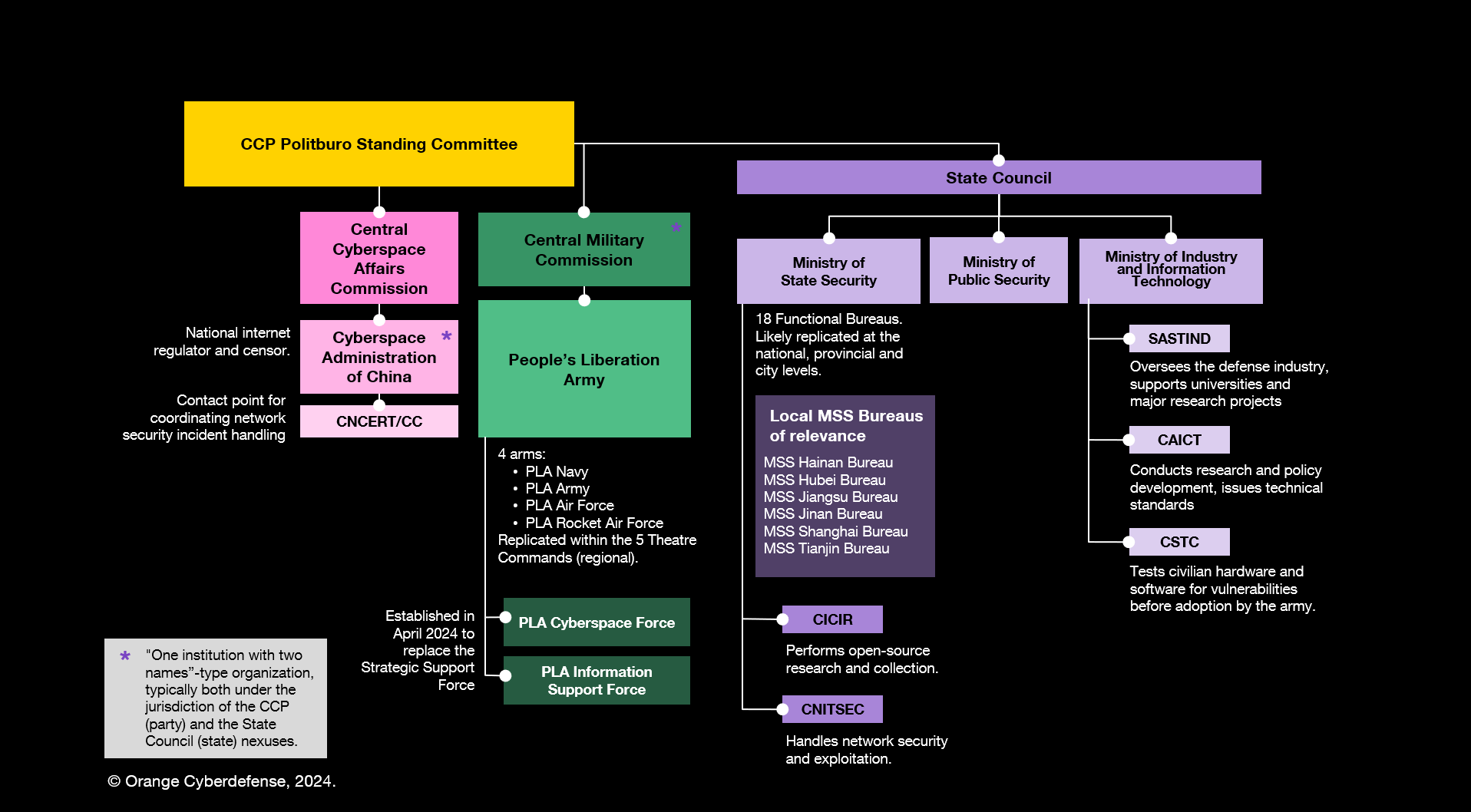

Understanding the cyber threats posed by China requires a closer examination of the state apparatus and how it progressively built its intelligence collection and cyber warfare capabilities from an institutional perspective. This process of shaping proper structures for planning and orchestrating cyberattacks took place over the last three decades, with the main stakeholders being:

- The People's Liberation Army (PLA),

- The Ministry of State Security (MSS),

- The Ministry of Public Security (MPS),

- The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT).

a. The People's Liberation Army (PLA)

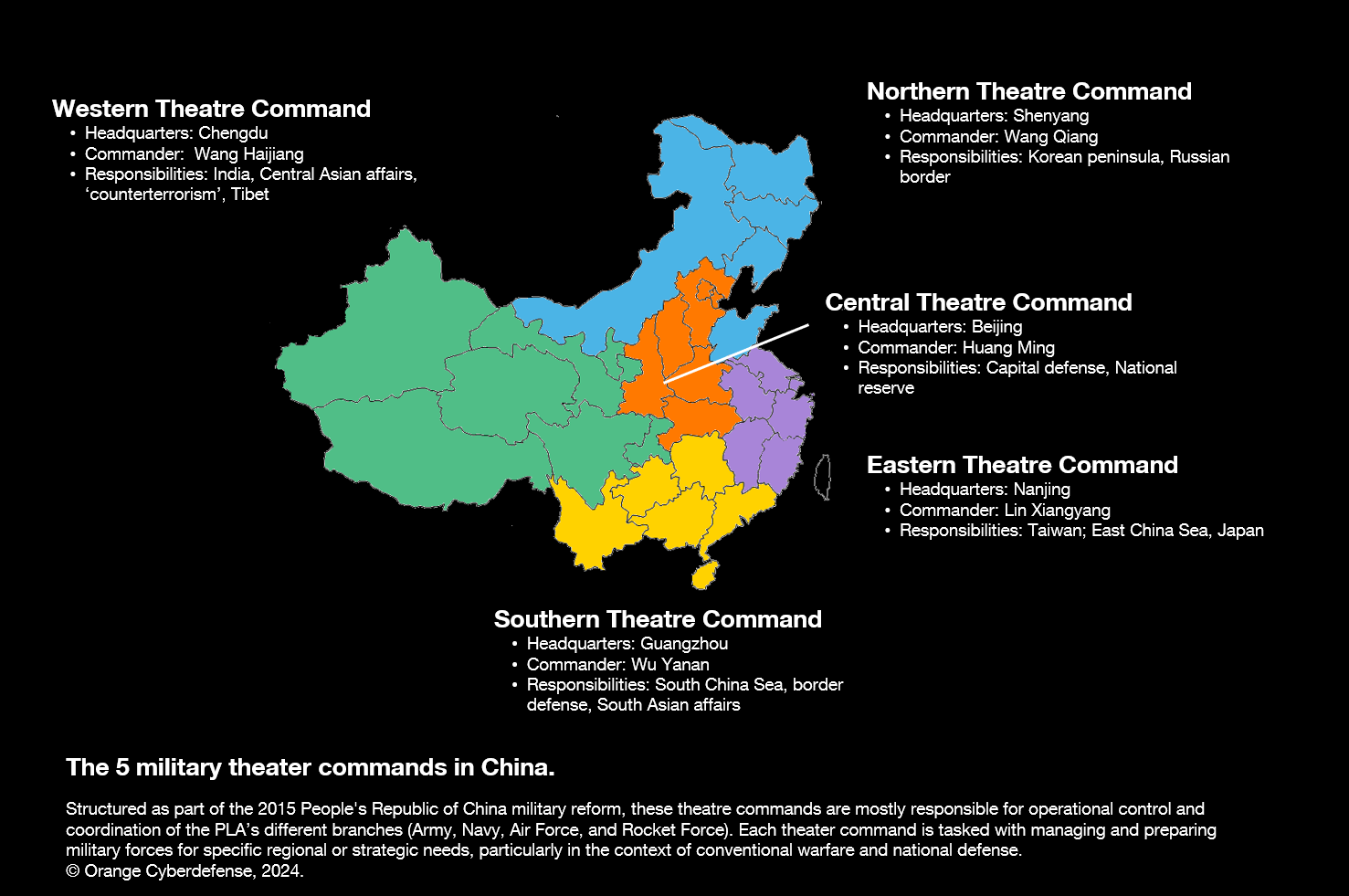

Subordinated to the Central Military Commission (the military command authority of the Communist Party's Central Committee), the PLA notably consolidated its SIGINT capabilities applied to cyberspace in the 2010s. While new cyberspace-related organizations emerged within the PLA in the mid-2000s, the 2015-2016 military reform fundamentally reshaped the PLA, most notably with the introduction of the Strategic Support Force (SSF). Clearly designed to bring advantages in cyber warfare, the SSF took over and merged into its Network Systems Department (NSD) many of the cyber espionage responsibilities and operational units from the former Third and Fourth Departments of the PLA. Some of these units, visible in our cartography, are infamous for being linked to specific APT clusters, following indictments and CTI reports on their malicious campaigns throughout the 2010s. On April 19, 2024, the Network Systems Department was reorganized as the independent PLA Information Support Force, along with the creation of PLA Cyberspace Force. As explained by Joe McReynolds and John Costello from the China Cyber and Intelligence Studies Institute, it's unclear how both entities' missions will be divided, with some clear overlaps expected, especially in intelligence gathering and electronic warfare.

b. The Ministry of State Security (MSS) and Ministry of Public Security (MPS)

Beyond the PLA, Chinese offensive cyber capabilities have been

introduced over the last 30 years by civil government

departments responsible for intelligence and security, namely

the Ministry of State Security (MSS) and the

Ministry of Public Security (MPS).

More importantly, the MSS and its decentralized regional

offices

serve

as both an internal security service and foreign intelligence

collection agency. Established in 1983, the MSS particularly

focuses on state stability issues (embodied by the "Three Evils"

of separatism, terrorism, and extremism). As

noted by Alex

Joske, the MSS' provincial organs are extremely important as

they tend to have far more personnel than the central Ministry,

and some degree of geographical specialization based on the

international connections of their region. Following successive

public reporting on PLA-attributed cyber operations in the early

2010s, the MSS began playing an increasingly prominent role in

conducting cyberespionage operations, including against

foreign targets.

According

to Adam Kozy, this shift was also due to the rise of the

increasingly efficient contractor model, with the MSS using a

mix of in-house talents and cyber contractors to carry out more

covert and advanced cyber espionage activities.

Meanwhile, the Ministry of Public Security is responsible for public law enforcement and political security since 1983. The MPS focuses on domestic affairs and operates in the cyber field because of its historic counterintelligence and computer crime investigations mandates.

One could also mention here the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), which regulates industrial IT policy and manages China's telecommunications, IT and network infrastructure affairs. In a way, the MIIT is also charged with developing the infrastructure, human capital, and technology necessary for the MSS and MPS, for instance through its State Administration of Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense (SASTIND) agency.

c. State capacity building and cooptation

Finally, as argued by Tim Maurer, author of 'Cyber Mercenaries: The State, Hackers, and Power', an essential dynamic that accompanied the restructuring of these state institutions was China's gradual progressive coopting of civilian hackers through institutionalized incentives. Indeed, the 1990s in China featured the rise of Internet and the emergence of first Chinese hacking groups, such as the Green Army founded in 1997, which gathered some 3,000 members. Initially condemned by the Chinese state, these hacktivist clusters were gradually tolerated and eventually encouraged and even protected by the state due to their patriotic alignment. From 2003 onwards, this growing hacking workforce was systematically incorporated into the PLA, MSS, and MPS via competitions, job postings on hacker forums, and more direct freelance-like participation in offensive operations. While these Chinese hackers mainly carried out web defacements and DDoS attacks until around 2006, these activities matured into more sophisticated data thefts operations under Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping's presidencies.

Overall, between the 1980s and the 2010s, the enhancement of Chinese cyberespionage capabilities relied on both the restructuring of historical state institutions as well as the progressive recruitment of patriotic hackers. This laid the foundation for what would become a "fully institutionalized militia", working hand-in-hand with the private sector and academia.

Private companies as hack-for-hire contractors

China boasts the world's second largest cybersecurity industry, valued at over $22 billion. While the hundreds of private cybersecurity providers reinforce China's status as a global security leader, several of them support the state more directly. The contracting spectrum can be very large, with private organizations engaging in cyberattacks against domestic and foreign entities of strategic interest for the PRC and others providing services that may facilitate them, ranging from infrastructure leasing, tool development, to hacking-for-hire...

The recent takedown of the Raptor Train botnet used by Chinese APTs for cyberespionage highlighted the involvement of the publicly-traded Chinese company Integrity Technology Group (ITG). The latter was clearly associated to a front-end application used to manage the bots. This collaboration is now standard practice, especially within the MSS, which leverages an extensive network of private sector connections.

a. Corporate contractors of varied size

Just like Integrity Technology Group, which was listed on the Shanghai stock exchange, China's top cyber contractors are often the country's industry leaders. Enterprises such as ThreatBook, Qihoo360, and Qi An Xin not only provide defensive security solutions to public agencies but are also believed to indirectly contribute to offensive cyber operations. Unlike those large firms, i-SOON belongs to a more numerous group of small to medium-sized entities. Despite their limited size, many Chinese SMEs tend to specialize in multiple cyber subdomains at once. For instance, i-SOON, reportedly employing only 72 workers before the leak, would offer services ranging from penetration testing and malware development to intelligence analysis and red team training.

These entities often act as subcontractors to the industry giants, filling the gap in their cyber offensive competencies and further fragmenting the hack-for-hire supply chain. The choice of subcontractors typically rests with the prime contractor, potentially influenced by personal relationships between the company executives, reflecting the Chinese cultural practice of guanxi (关系). These smaller companies also take on contracts directly from the state, particularly from regional and municipal government agencies.

These contractors operate in a fiercely competitive environment, constantly fighting for state contracts. Yet, despite this rivalry, collaboration is not uncommon: i-SOON, for example, procured a vulnerability affecting the QQ messaging platform for an intrusion campaign from NoSugarTech, its competitor co-founded by Qihoo360. These complex dynamics of competition and cooperation can occasionally lead to legal conflicts, as seen when APT41-linked Chengdu 404 sued i-SOON over intellectual property rights violations.

b. Opportunities and risks of contracting

The inclusion of private enterprises in the PRC's hacking operations provides the Chinese state with several strategic advantages. One key benefit is plausible deniability; when an attack is traced back to a private company, it may be more challenging for Western authorities to establish a direct link to the Chinese government. Even after companies like Chengdu 404 are sanctioned by foreign governments, they often continue their operations within China and may even receive financial support from the state, allowing them to maintain business as usual. Significantly, private contractors offer the state access to a pool of hacking talent within the private sector, bringing cyber offensive expertise that may not be readily available within governmental agencies.

However, this intricate web of public-private relationships also introduces significant risks. While government and military units typically adhere to strict security standards, ensuring the same level of compliance among private contractors and their subcontractors is more challenging. Although obtaining secrecy certifications and government-approved certified supplier status is needed for state contracts and cyber weapons production, effective auditing and supervision of providers gets harder with further fragmentation of the supply chain. This can lead to inconsistencies in cyber hygiene and Operational Security measures, increasing the likelihood of errors that could expose sensitive cyber operations or their sponsors.

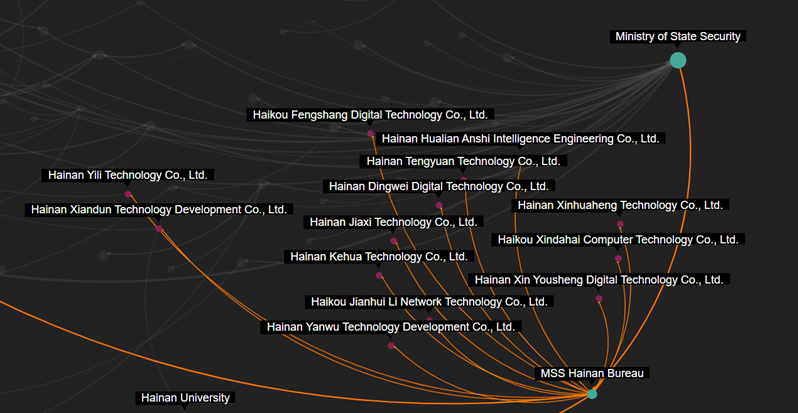

c. "Front" companies

It is important to note, however, that not all corporate entities linked to Chinese state-sponsored cyberattacks can be considered contractors in real terms. In many instances, individuals linked to the MSS or PLA units register fake companies to obscure the attribution of their campaigns to the Chinese state. These fake enterprises, which engage in no real profit-driven activities, may help procure digital infrastructure needed for conducting the cyberattacks without drawing unwanted attention. They also serve as fronts for recruiting personnel for roles that support hacking operations.

Distinguishing between genuine contractors and front companies can prove challenging, particularly when dealing with smaller enterprises that have limited online presence or business transparency. While some subcontractors might openly advertise their grey-market services, this is not always the case. A lack of open-source information about a company doesn't automatically indicate it's a front for state-backed hacking. However, there are often telltale signs suggesting certain entities are not legitimate registered companies. For instance, 13 front enterprises linked to APT40 shared similar names and were registered by the same individuals or to the same addresses.

Universities as hubs for offensive security research

Recognizing the critical nature of cybersecurity, the Chinese government has increasingly emphasized the role of educational institutions in advancing the country's cyber capabilities. This was clearly highlighted in 2017, when China began certifying select universities as World-Class Cybersecurity Schools, and further solidified in the 14th Five-Year Plan for the years 2021-2025.

This emphasis reveals a dual implication. Naturally, the proliferation of cybersecurity programs at universities has allowed China to form new security cadres and bolster the nation's cyber defense posture. More significantly, however, universities have also emerged as hubs for offensive security research that can be leveraged by state authorities. Additionally, some academic institutions have evolved into incubators for cyber threat groups, channeling young talents into APT-related public and private entities.

a. Participation in cyber offensive efforts

Like many other nations, China maintains several military universities that work closely with the armed forces. It comes as no surprise, for instance, that the PLA Information Engineering University has been involved in a project aiming at testing malware effectiveness for the military, while the National University of Defense Technology hosts a lab focused on electromagnetic interference against information systems.

Additionally, other universities play a crucial role in the development of cyber ranges, often in collaboration with private enterprises and the military. Cyber ranges are virtual environments consisting of interconnected virtual machines that simulate real-world computer networks, allowing users to practice security operations and hone their skills in a controlled setting. For example, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, in collaboration with cyber range complex Peng Cheng Lab, has conducted advanced research on the use of AI in cybersecurity using a supercomputer. The school is among the most advanced in research at the intersection of AI and cyberspace, alongside Hainan University and Southeast University.

More striking, however, is the extent of collaboration between military structures and civilian universities for offensive operations directly. Several schools, such as Southeast University or Xidian University, have received research grants from the PLA for information security R&D and have directly contributed to the army's operational capabilities. In some cases, universities' infrastructure may be leveraged by state-linked threat actors. For example, Unit 61726 of the Third Department of the PLA, known as Circuit Panda, allegedly used Wuhan University's facilities for cyber operations targeting Taiwanese entities. Among the C9 League universities – the nine most prestigious Chinese universities enjoying robust state funding – only Fudan University has yet to be linked to any state-sponsored offensive security operations.

(Fudan University, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Harbin Institute of Technology, Nanjing University, Peking University, Tsinghua University,

University of Science and Technology of China, Xi'an Jiaotong University, and Zhejiang University)

b. Talent pipeline for the state and contractors

One of the most critical roles of higher education institutions in China's offensive cybersecurity ecosystem is to supply young talent to the PLA and Ministry of State Security units, as well as to private contractors. For instance, Unit 61398 of the Third Department of the PLA, associated with APT1, aggressively recruited from universities like Zhejiang University and Habrin Institute of Technology, offering attractive career opportunities in cybersecurity, intelligence and specialized training programs. For the same reasons, leading civilian institutions like Tsinghua University have collaboration programs with military academies, aligning their cyber training curricula with the state's operational needs.

Beyond direct hacking roles, recent university graduates are reportedly being recruited for complementary tasks that contribute to cyber operations indirectly. These includes translation of stolen documents or gathering open-source intelligence on potential victims, particularly to facilitate spear phishing attacks. In one such case, the front company Hainan Xiandun operated by APT40 recruited recent English language graduates for espionage-related work, without the recruits knowing the true nature of the company's activities.

Hacking competitions serve as yet another recruitment pipeline for private contractors and state entities, as evidenced by the recently published deep-dive report and tracker by Dakota Cary (Nonresident Fellow at the Atlantic Council's Global China Hub) and Eugenio Benincasa (Senior Researcher at ETH Zurich Center for Security Studies). Renowned teams from top universities, such as Blue Lotus from Tsinghua University or 0ops from Shanghai Jiao Tong University, frequently compete in or organize these events, demonstrating their red team skills to potential employers. Some team members would later establish their own cybersecurity companies. Meanwhile, these competitions also benefit the state and its operational needs more directly, both for talent spotting or to repurpose vulnerabilities and techniques discovered by the student groups in state-sponsored cyber campaigns (more on that in Section 4). For instance, Cary and Benincasa described how the Wangding Cup or the CTFWar practice platform and competition is likely used by the MSS and MPS as a talent-recruitment pool.

A telling case of the vulnerability gathering system

No other example illustrates the integration of private security companies and universities into China's state cybersecurity framework better than the vulnerability disclosure ecosystem.

a. Network of vulnerability databases

This versatile and exceptionally well-organized system, analyzed in depth by researchers Dakota Cary and Kristin Del Rosso, relies on several interconnected vulnerability databases. The China National Vulnerability Database (CNVD) is managed by CNCERT/CC, China's central incident response team. Its collected vulnerabilities are channeled to its technology collaboration organizations, including some known offensive contractors for the PLA and MSS. It is quite telling that among the three main partner sub-databases from which CNVD gathers vulnerabilities, one is operated by the industry giant Qi An Xin, while another - by Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

Another significant database, CNNVD, or China National Vulnerability Database of Information Security, is particularly susceptible to be used in offensive campaigns. CNNVD is managed by CNITSEC, a cover identity of the 13th Bureau of the MSS. It receives vulnerabilities from at least 150 private sector partners, categorized into three tiers based on their capacities and frequency of bug submissions. According to Recorded Future, the MSS likely withholds selected high-value flaws for its own needs, with anecdotal evidence suggesting suspicious patterns in CNNVD's reporting time. For example, analyst Adam Kozy noted that the threat group KRYPTONITE PANDA exploited a critical Microsoft Office vulnerability (CVE-2018-0802) a month before its disclosure to the vendor by Qihoo 360, which initially discovered the flaw.

The vulnerability management ecosystem underwent significant changes in 2021, with the introduction of the “Regulations on the Management of Network Product Security Vulnerabilities”, or RMSV. This regulation prohibits researchers from disclosing vulnerabilities publicly or to the affected vendor without first consulting the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT). Under this framework, vulnerabilities are now funneled to the MIIT-managed Vulnerability Information Sharing Platform (NVDB) via several sub-databases, such as the ICS VulnerabilityDatabase and the Mobile Applications Vulnerability Database. This development increases the risk of zero-day exploitation in China's state-sponsored hacking campaigns. Despite this, Chinese researchers continue to regularly submit flaws in foreign products to vendors like Microsoft and Apple.

b. Impact of hacking competitions

An overview of this ecosystem would not be complete without taking a closer look at hacking competitions. As evidenced by Eugenio Benincasa, these events serve not only as cyber talent incubators but also as direct sources of cutting-edge vulnerabilities provided by competing teams.

Chinese universities like Tsinghua and Shanghai Jiao Tong have become leaders in this field, hosting renowned teams such as Blue Lotus and 0ops. Initially competing in international hacking contests like DEFCON and Pwn2Own, these teams have over time contribute to the growing number of domestic competitions in China, such as the brand-new Matrix Cup. Graduates of these teams have often gone on to establish their own cybersecurity enterprises, many of which are now leading contributors to state vulnerability databases.

Some companies, such as Tencent, have formed their own dedicated CTF teams, while others, including i-SOON, have been heavily sponsoring existing CTF events or even establishing their own (e.g. Anxun Cup). Moreover, these competitions are often the result of strong partnerships between industry leaders and academic institutions. A notable example is the TOPSEC Cup, which was co-organized by Beijing Topsec, a known PLA contractor, in partnership with Southeast University. In one instance, its participants were tasked with infiltrating the networks of VAE Inc., a U.S. Department of Defense contractor.

Targets of these exercises are often strategically selected to align with the state's cyber interests, focusing on entities that later become priorities of APT hacking campaigns. Consequently, the vulnerabilities and exploits discovered during the events have, on several occasions, been repurposed for state-sponsored cyber campaigns. For instance, the "Chaos" exploit, developed by Zhao Qixun during the 2021 Tianfu Cup, was reportedly shared with Chinese state agencies, and later used in targeted attacks against Uyghurs before any patches were released. Similarly, a Microsoft Exchange vulnerability (CVE-2021-42321), demonstrated at the same event but not detailed publicly, was exploited in the wild just days after the competition. Leaks from i-SOON further confirm that vulnerabilities identified during the 2021 event were transferred to the Ministry of Public Security, proving the integral role of CTF events in China's offensive security ecosystem.

Using our interactive map

This report accompanies an interactive map released on the Orange Cyberdefense CERT Research website. This visualization tool is designed to illustrate the complex relationships within the Chinese cyber ecosystem. As of October 2024, the map includes over 300 nodes, namely:

- Chinese state entities (42)

- Vulnerability Databases (12)

- Private companies (171)

- Front companies (19)

- Universities (24)

- Cyber Competitions (39)

- Civilian Hacking groups (7)

- Cyber Ranges (2)

The map is fully interactive, allowing users to easily explore nodes using mouse navigation or search filters such as tags, location, and pipelines. Tags include identifiers of intrusion sets and/or known threat groups, including:

- APT1

- APT2

- APT3

- APT10

- APT14

- APT17

- APT19

- APT26

- APT27

- APT30

- APT31

- APT40

- APT41

- Circuit Panda

- Nomad Panda

- Dragnet Panda

- Stalker Panda

- Karma Panda

- Ethereal Panda

- LuckyCat

Pipelines designate all nodes associated to activities surrounding the CNNVD and CNVD vulnerability databases. CNNVD contributors are split into the three tiers mentioned above.

Locations refer to both the specific city (if known) where the actor is located, as well as the broader region. We have chosen to regroup these locations into five theaters, aligned with the military theater commands of the PLA. This consolidation can be particularly insightful as it illustrates the distinct focuses and areas of targeted operations, including for non-PLA nodes.

More than 400 relationships are featured and detailed, each represented by clickable arrows that link the nodes, as well as listed in each node's description. Each relationship is accompanied by a detailed description and a confidence level (low, medium, high), based on our assessment of the source's overall reliability or relevance.

The data for these nodes and relationships come from a broad analysis of publicly available academic publications, open-source intelligence (OSINT), and CTI literature on the Chinese cyber ecosystem. This project is the result of more than 8 months of research, data collection and analysis. However, it is important to remember that the map will never be exhaustive, due to our limited visibility and to the very nature of this obscure threat ecosystem.

Users can partially download the underlying database through the “Export” button located on the left of the query panel if needed.

Sources

- Adam KOZY, "Two Birds, One STONE PANDA", CrowdStrike, 08/30/2018.

- Adam KOZY, "Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Hearing on "China's Cyber Capabilities: Warfare, Espionage, and Implications for the United States", 02/17/2022.

- Alex JOSKE, "State security departments: The birth of China's nationwide state security system", in Deserepi: Studies in Chinese Communist Party external work, 09/27/2023.

- Alex JOSKE, Charlie Lyons JONES, Audrey FRITZ, Elsa KANIA and Dr Samantha HOFFMAN, "China Defence Universities Tracker", Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 11/25/2019.

- Dakota CARY, "Academics, AI, and APTs How Six Advanced Persistent Threat-Connected Chinese Universities are Advancing AI Research", Center for Security and Emerging Technology, 03/2021.

- Dakota CARY, "China's CyberAI Talent Pipeline", Center for Security and Emerging Technology, 07/2021.

- Dakota CARY, "Downrange: A Survey of China's Cyber Ranges", Center for Security and Emerging Technology, 09/2022.

- Dakota CARY, "Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Hearing on "China's Cyber Capabilities: Warfare, Espionage, and Implications for the United States", 02/17/2022.

- Dakota CARY, Aleksandar MILENKOSKI, "Unmasking I-Soon - The Leak That Revealed China's Cyber Operations", SentinelOne, 02/21/2024.

- Dakota CARY, Eugenio BENINCASA , "Capture the (red) flag: An inside look into China's hacking contest ecosystem", Atlantic Council, 10/18/2024.

- Dakota CARY, Eugenio BENINCASA ,"Capture the (red) flag: How hacking contests enhance China's cyber capabilities", Atlantic Council, 10/18/2024 .

- Dakota CARY, Kristin DEL ROSSO, "Sleight of hand: How China weaponizes software vulnerabilities", Atlantic Council, 09/06/2023.

- Eleanor OLCOTT, Helen WARELL, "China lured graduate jobseekers into digital espionage", Financial Times, 06/30/2022.

- Eugenio BENINCASA, "From Vegas to Chengdu: Hacking Contests, Bug Bounties, and China's Offensive Cyber Ecosystem", Center for Security Studies (CSS) of ETH Zürich, 06/2024.

- Farmpoet, "Twitter", 08/22/2024.

- HarfangLab, "A comprehensive analysis of I-Soon's commercial offering", 03/01/2024.

- Insikt Group, "China's Cybersecurity Law Gives the Ministry of State Security Unprecedented New Powers Over Foreign Technology", Recorded Future, 08/31/2017.

- Insikt Group, "China's Ministry of State Security Likely Influences National Network Vulnerability Publications", Recorded Future, 11/16/2017.

- Intrusion Truth, "What is the Hainan Xiandun Technology Development Company?", 01/09/2020.

- Joe MCREYNOLDS, John COSTELLO, "Planned Obsolescence: The Strategic Support Force In Memoriam (2015-2024)", China Brief, Volume: 24 Issue: 9, 04/26/2024.

- John CHEN, "Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Hearing on "China's Cyber Capabilities: Warfare, Espionage, and Implications for the United States"," 02/17/2022.

- Ken DUNHAM, Jim MELNICK, "'Wicked Rose' and the NCPH Hacking Group", 11/2012.

- Mandiant, "APT1: Exposing One of China's Cyber Espionage Units", 02/19/2013.

- Michael DAHM, "A Disturbance in the Force: The Reorganization of People's Liberation Army Command and Elimination of China's Strategic Support Force", China Brief, Volume: 24 Issue: 9, 04/26/2024.

- Microsoft, "Microsoft Digital Defense Report 2022", 11/04/2022.

- Natto Team, "i-SOON: "Significant Superpower" or Just Getting the Job Done?", 03/08/2024.

- Natto Team, "i-SOON: Another Company in the APT41 Network", 10/27/2023.

- Natto Team, Eugenio BENINCASA, "Matrix Cup: Cultivating Top Hacking Talent, Keeping Close Hold on Results", 07/24/2024.

- Nigel INKSTER, "The Chinese Intelligence Agencies: Evolution and Empowerment in Cyberspace", in China and Cybersecurity: Espionage, Strategy, and Politics in the Digital Domain, 04/23/2015.

- Nigel INKSTER, China's Cyber Power, 05/06/2016.

- Patrick HOWELL O'NEILL, "How China turned a prize-winning iPhone hack against the Uyghurs", MIT Technology Review, 05/06/2021.

- Robert SHELDON, Joe MCREYNOLDS, "Civil-Military Integration and Cybersecurity: A Study of Chinese Information Warfare Militias", in China and Cybersecurity: Espionage, Strategy, and Politics in the Digital Domain, 04/23/2015.

- Stewart SCOTT, Sara Ann BRACKETT, Yumi GAMBRILL, Emmeline NETTLES, Trey HERR, "Dragon tails: Preserving international cybersecurity research", Atlantic Council, 09/14/2022.

- ThreatConnect, "The Anthem Hack: All Roads Lead to China", 02/27/2015.

- Tim MAURER, "Change Over Time: China's Evolving Relationships with Cyber Proxies", in Cyber Mercenaries: The State, Hackers, and Power, 12/21/2017.

- US Justice Department, "Seven International Cyber Defendants, Including "APT41" Actors, Charged In Connection With Computer Intrusion Campaigns Against More Than 100 Victims Globally", 09/16/2020.

- US Treasury, "Treasury Sanctions China-Linked Hackers for Targeting U.S. Critical Infrastructure", US government, 03/25/2024.

- Winnona BERNSEN, "Same Same, but Different", Margin Research, 02/29/2024